The Department of Neurosurgery at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital of Mekelle University treats over 1000 significant head injuries every year including performing an average of 2.5 operations per day. All patients should undergo standard multiple trauma resuscitation and assessment by Advanced Trauma Life Support Guideline.

Since 2015 the Department of Neurosurgery at Mekelle University has instituted a standard head injury protocol (now revised in 2019) for the assessment and treatment of children and adults at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital based in part upon the local settings of Northern Ethiopia and the international guidelines including that of the Brain Trauma Foundation

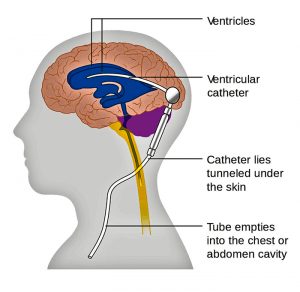

Intracranial pressure monitoring is not economically feasible in Ethiopia but we are developing research protocols to look at optic nerve sheath diameter by serial ultrasound in the near future.

Adults Initial Assessment

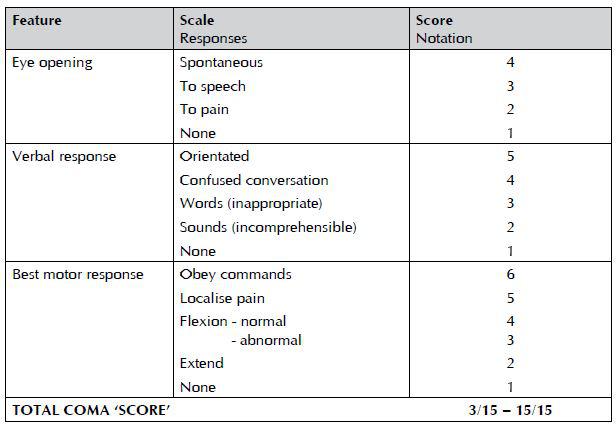

The management of patients with a head injury should be guided by clinical assessments and protocols based on the Glasgow Coma Scale and Glasgow Coma Scale Score.

Indications for referral to hospital

Adult patients with any of the following signs and symptoms should be referred to an appropriate hospital for further assessment of potential brain injury:

1. GCS<15 at initial assessment (if this is thought to be alcohol related observe for two hours and refer if GCS score remains<15 after this time)

post-traumatic seizure (generalized or focal) focal neurological signs

2. signs of a skull fracture (including cerebrospinal fluid from nose or ears,

hemotympanum, boggy hematoma, post auricular or periorbital bruising)

3. loss of consciousness

4. severe and persistent headache

5. post-traumatic amnesia >5 minutesrepeated vomiting (two or more occasions)

6. retrograde amnesia >30 minutes

7. high risk mechanism of injury (road traffic accident, significant fall)

coagulopathy, whether drug-induced or otherwise.

Indications for head CT scan

Immediate CT scanning should be done in an adult patient who has any of the following features:

1. eye opening only to pain or not conversing (GCS 12/15 or less)

2. confusion or drowsiness (GCS 13/15 or 14/15) followed by failure to improve within at most one hour of clinical observation or within two hours of injury (whether or not intoxication from drugs or alcohol is a possible contributory factor)

3. base of skull or depressed skull fracture and/or suspected penetrating injuries

4. a deteriorating level of consciousness or new focal neurological signs

full consciousness (GCS 15/15) with no fracture but other features, eg

— severe and persistent headache

— two distinct episodes of vomiting

5. a history of coagulopathy (eg warfarin use) and loss of consciousness, amnesia or any neurological feature.

CT scanning should be performed within eight hours in an adult patient who is otherwise well but has any of the following features:

1. age>65 (with loss of consciousness or amnesia)

2. clinical evidence of a skull fracture (eg boggy scalp haematoma) but no clinical features indicative of an immediate CT scan

3. any seizure activity

4. significant retrograde amnesia (>30 minutes)

5. dangerous mechanism of injury (pedestrian struck by motor vehicle, occupant ejected from motor vehicle, significant fall from height) or significant assault (eg blunt trauma with a weapon).

In adult patients who are GCS<15 with indications for a CT head scan, scanning should include the cervical spine.

Indications for admission to hospital

An adult patient should be admitted/observed to hospital if:

1. the level of consciousness is impaired (GCS<15/15)

2. the patient is fully conscious (GCS 15/15) but has any indication for a CT scan (if the scan is normal and there are no other reasons for admission, then the patient may be considered for discharge)

3. the patient has significant medical problems, eg anticoagulant use

4. the patient has social problems or cannot be supervised by a responsible adult.

Referral to neurosurgical unit

A patient with a head injury should be discussed with a neurosurgeon:

1. when a CT scan in a general hospital shows a recent intracranial lesion

when a patient fulfills the criteria for CT scanning but facilities are unavailable

2. when the patient has clinical features that suggest that specialist neuroscience assessment, monitoring, or management are appropriate, irrespective of the result of any CT scan.

3. All salvageable patients with severe head injury (GCS score 8/15 or less) should be

4. transferred to, and treated in, a setting with 24-hour neurological ICU facility.

Children

Initial assessment

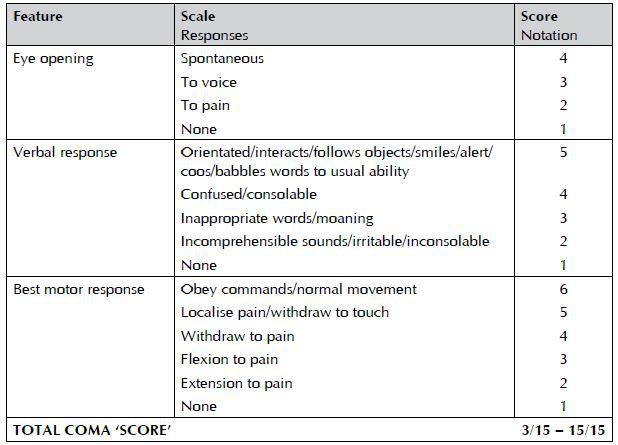

Great care should be taken when interpreting the Glasgow Coma Scale in the

under fives and this should be done by those with experience in the management of the young child.

Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale and Scoring

(for use in patients under five years of age)

Indications for referral to hospital

In addition to the indications for referral of adults to hospital, children who have sustained a head injury should be referred to hospital if any of the following risk factors apply:

1. clinical suspicion of non-accidental injury

2. significant medical co-morbidity (eg learning difficulties, autism, metabolic disorders)

3. difficulty making a full assessment

4. not accompanied by a responsible adult

5. social circumstances considered unsuitable.

Indications for head CT scan

Immediate CT scanning should be done in a child (<16 years) who has any of the following features:

1. GCS≤13 on assessment in emergency department

2. witnessed loss of consciousness >5 minutes

3. suspicion of open or depressed skull injury or tense fontanel

4. focal neurological deficit

5. any sign of basal skull fracture.

CT scanning should be considered within eight hours if any of the following features are present (excluding indications for an immediate scan):

1. presence of any bruise/swelling/laceration >5 cm on the head

2. post-traumatic seizure, but no history of epilepsy nor history suggestive –of reflex anoxic seizure

–amnesia (anterograde or retrograde) lasting >5 minutes

–clinical suspicion of non-accidental head injury

–a significant fall

–age under one year: GCS<15 in emergency department assessed by

–personnel experienced in paediatric GCS monitoring

–three or more discrete episodes of vomiting

–abnormal drowsiness (slowness to respond).

If a child meets head injury criteria for admission and was involved in a high speed road traffic accident, scanning should be done immediately

Indications for admission to hospital

Children who have sustained a head injury should be admitted to hospital if any of the following risk factors apply:

1. any indication for a CT scan

2. suspicion of non-accidental injury

3. significant medical co-morbidity

4. difficulty making a full assessment

5. child not accompanied by a responsible adult

6. social circumstances considered unsuitable.

Referral to neurosurgical unit

A patient with a head injury should be discussed with a neurosurgeon:

1. when a CT scan in a general hospital shows a recent intracranial lesion

2. when a patient fulfills the criteria for CT scanning but facilities are

unavailable

3. when the patient has clinical features that suggest that specialist

neuroscience assessment, monitoring, or management are appropriate,

irrespective of the result of any CT scan.

4. All salvageable patients with severe head injury (GCS score 8/15 or less) should be transferred to, and treated in, a setting with 24-hour neurological ICU facility.

In hospital care

All medical and nursing staff involved in the care of patients with a head injury should be trained and competent in the use and recording of the Glasgow Coma Scale.

The GCS should not be used in isolation and other parameters should be considered along with it, such as:

–pupil size and reactivity

–limb movements

–respiratory rate and oxygen saturation

–heart rate

–blood pressure

–temperature

–unusual behavior or temperament or speech impairment.

Family members and friends should be used as a source of information.

Observations should be recorded on a chart

Children <3 years old who have sustained a head injury are particularly difficult to evaluate and clinicians should have a low threshold of suspicion for early consultation with a specialist pediatric unit.

Children who are admitted should be under the care of a multidisciplinary team that includes a pediatric trained doctor experienced in the care of children with a head injury.

Children should be observed on a children’s ward.

The risk of rapid deterioration is greatest in the first six hours after injury and then decreases. If the patient is admitted on the first day of the injury then repeat evaluation every few hours is indicated if high risk factors such as high energy injury, Glasgow coma scale < 15, or focal neurological deficit is present.

Medical staff should assess the patient on admission to the ward and should re-assess the patient at least once within the next 24 hours. Assessment should include: examination for the GCS, neck movement, limb power, pupil reactions, all cranial nerves and signs of basal skull fracture.

Any of the following examples of neurological deterioration should prompt urgent re-appraisal by a doctor:

–the development of agitation or abnormal behavior

–a sustained decrease in conscious level of at least one point in the motor or verbal response or two points in the eye opening response of the GCS score

–the development of severe or increasing headache or persisting vomiting

new or evolving neurological symptoms or signs, such as pupil inequality or

asymmetry of limb or facial movement.

If re-assessment confirms a neurological deterioration, many factors need to be evaluated but the first step is to ensure the airway is clear, and that oxygenation and circulation are adequate.

Clinical signs of shock in a patient with a head injury should be assumed, until proven otherwise, to be due to hypovolemia caused by associated injuries.

Whilst an intoxicating agent may confuse the clinical picture, the assumption that deterioration or failure to improve is due to drugs or alcohol must be resisted.

If systemic causes of deterioration such as hypoxia, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, or hypoglycemia can be excluded, then resuscitation should continue according to accepted trauma protocols.

After traumatic brain injury, agitation may be a sign of neurological deterioration, hypoxia, electrolyte disturbance, drug/alcohol withdrawal, or seizures. Medical evaluation should be done in conjunction with pharmacological therapy for behavior.

Therapeutic Goals and Interventions

Systolic BP < 90 mm Hg and O2 Saturation < 90% should be avoided.

Mannitol

Mannitol in doses of 0.25gram/kg to 1.0gram/kg may reduce ICP. Our usual regimen is to give an initial dose of 1.0 gram/kg and the start 0.25mg/kg every 8 hours. The dose can be increased up to 1.0 gram/kg and frequency up to every 6 hours as needed. It is most useful as a temporizing measure such as to treat a patient suspected of having a mass lesion which may be surgical while preparing that patient for surgery. It is most effective in bolus doses rather constant infusion which may be repeated every 6 hours. Most of the world wide experience deals with controlling intracranial pressure which is being monitored. It should not be a part of routine head injury management. Side effects of hypotension, increases in size of intraparenchymal brain hemorrhage, and kidney dysfunction may occur.

The use of mannitol for head injury treatment in developing countries without ICP monitoring has not been well studied.

Indications:

1. Salvageable Head Injury with GCS 8 or less.

2. Deterioration from GCS > 8 to less for three days as above

3. Pre-operative .25gram/kg to 1.0gram/kg dose for suspected or known mass lesion. May be repeated intra-operatively.

4. Post-operative management of cerebral edema

Enteral feeding should be begun by 72 hours after injury. Hyperglycemia should be avoided as increased intracellular lactic acidosis can worsen brain injury.

Seizures and Seizure Prophylaxis

Prophylactic anticonvulsants does not reduce late seizure development or improve outcomes. However we face an unusual situation in Ethiopia where there are no intravenous anticonvulsants. We have had experiences of a few patients in the past few years whose developed early onset post traumatic seizures which where difficult to control while we were waiting for oral phenytoin to be absorbed which typically takes about 24 hours. Therefore we are changing our previous recommendation to start phenytoin or carbamezipine in any patient with an abnormal brain finding on CT Scan of the brain and continue for 7 days.

Anticonvulsant treatment indications:

Phenytoin use according to body mass and age for a seizure in the first few days and continued for one week.

Craniotomy for intraparenchymal lesion (evacuation of hemorrhagic contusion or lobectomy) or if a dural tear is discovered such as for depressed fracture

Infection Prophylaxis

Routine single dose of Ceftriaxzone 1 gm IV on call for adults and 50mg/Kg in children for closed head injuries requiring surgery.

Single dose of periprocedural antibiotics for intubation only unless the patient has signs of aspiration pneumonia already present.

DVT Prophylaxis

Low molecular weight heparin is contraindicated in the presence of acute head injury. If there is no large hematoma (intraparenchymal) then generally should wait at least five days before beginning low dose heparin 5,000 units BID or low molecular weight heparin Graduated stockings or pneumatic compression stockings if available are appropriate.

Hyperventilation

Profound hypercarbia may increase ICP and profound hypocarbia may decrease cerebral perfusion. Hyperventilation is to be avoided in the first 24 hours after injury. Temporary mild hyperventilation pre-operatively or intra-operatively may be used.

Steroids

There is no sound scientific evidence supporting the use of steroids for head injury.

Barbiturates

Under special circumstances such as post-operative swelling or diffuse cerebral swelling in a viable patients in consultation with neurosurgical staff pentobarbital at 3mg/kg/ hour may be given for up to three days to attempt to control brain swelling. Patients who have bilateral dilated pupils and decreased brain stem function are not candidates for this treatment modality.

Post-Traumatic Meningitis

Most of the studies suggest post-traumatic meningitis can be treated similar to community acquired bacterial meningitis with Ceftriaxzone 1 gm Q12h in adults. If no response is seen consideration can be given to adding Vancomycin and Meripenum for resistant organism. In our experience most patients respond to a 10 day course of Ceftriaxzone. Consideration can be given to performing a lumbar puncture for culture and sensitivity if CT Scan shows no mass effect. If staph aureus is identified then treatment should be extended for 21 days duration.

Surgical Management Guidelines

Note: The clinical progression of the patient must always be considered strongly in decision to do surgery or treat conservatively. Lesions affecting the temporal lobe area are at high risk of rapid deterioration especially within the first three days after injury.

Epidural hematoma

–An epidural hematoma greater than 30 cm squared should be evacuated regardless of GCS score

–An epidural hematoma less than 30 cm squared, midline shift less than 5mm, and thickness less than 15 mm in a patient without neurological deficit can usually be considered for nonsurgical treatment if clearly clinically stable

–Acute epidural hematoma is best treated by craniotomy rather then burr holes. Tacking up of the dura to prevent rebleeding should be done.

Acute Subdural Hematoma

–An acute subdural hematoma with a thickness greater than 10 mm or midline shift greater than 5 mm should be evacuated regardless of GCS score

–Patients who have a large parenchymal contusion and acute subdural less than 10mm with an admission GCS< 9 and then subsequent deterioration may be a candidate for surgery.

–In severe cases of brain swelling. Bone flap removal and duraplasty may be necessary.

Surgery for Traumatic Intraparenchymal Lesions

–Surgery for resection of intraparenchymal lesions is not within the normal procedure guidelines for general surgery.

–Patients with focal intraparenchymal lesions who present with a GCS of 8 will be initially placed on medical management protocols.

–Patients with a GCS of 8 who deteriorate despite medical management will be discussed with the neurosurgical staff as regards to management

Chronic Subdural Hematoma

–A totally asymptomatic patient with evidence of a chronic subdural hematoma may be conservatively followed

–A symptomatic patient with chronic subdural hematoma should undergo timely operation

–The best outcome in chronic subdural hematoma was found in a prospective study utilizing the two burr hole technique with subdural drain placement. At Ayder an initial burr hole will placed frontally or parietally depending upon where the greatest thickness of the hematoma is found. If after irrigation of the subdural space the brain does not expand to the dura then a second burr hole will be placed. If the clot is gelatinous then the burr holes will be converted to a craniotomy. A pediatric feeding tube will always be place in the subdural space at least one centimeter beyond the proximal last side hole and exited through a separate stab wound.

–The subdural drain may be removed when the old blood drainage converts to CSF. The drain should be removed by the morning of the third day after surgery.

–After surgery while the subdural drain is in place the patient’s head should be kept flat to maximize brain re-expansion which will push out the remaining subdural hematoma

–If patient deteriorates following surgery after initial improvement or fails to improve then consideration for a repeat CT scan should be done.

Closed Depressed Skull Fracture

–Patients with a closed depressed fracture with a depression less than 1 cm and no neurological findings or associated hematoma requiring surgery are potential candidates for conservative treatment

–A closed depressed fracture with a depression 1 cm or greater (which is deeper then the inner table) and/or neurological deficit should under go timely surgical intervention.

–Patients with simple depressed fractures without dural tear or cerebral contusion require only routine pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and no anticonvulsant prophylaxis.

Open Depressed Skull Fracture

–Patients with an open depressed fracture greater than the depth of the calvarium should undergo surgery.

–Operation should be done within the first 48 hours after injury to reduce the risk of infection.

–The bone flap or fragments should be cleaned with betadiene and saline thoroughly before replacement

–A water tight closure of the dura should be attempted..

–Debridement of nonviable and contaminated brain should be done.

–A 24 hour course of intravenous Ceftriaxzone and Metronidazole should be given for cases where there is only minimal contamination and the dura is intact. Patients will then receive a 7 day oral course of Amoxicillin and Clavulanate (Augmentin) 500 mg every 8 hours for adults.

–An 7 day course of intravenous Ceftriaxzone and Metronidazole should be given for cases where there is extradual purulence, gross contamination or penetration of the brain especially if surgery was delayed more than 48 hours after injury.followed by a one week course of Augmentin orally.

–Post traumatic cerebritis or abscess requires 6 week course of intravenous antibiotics.

–Anticonvulsant prophlaxis should be given to all patients with dural laceration and open brain injury.