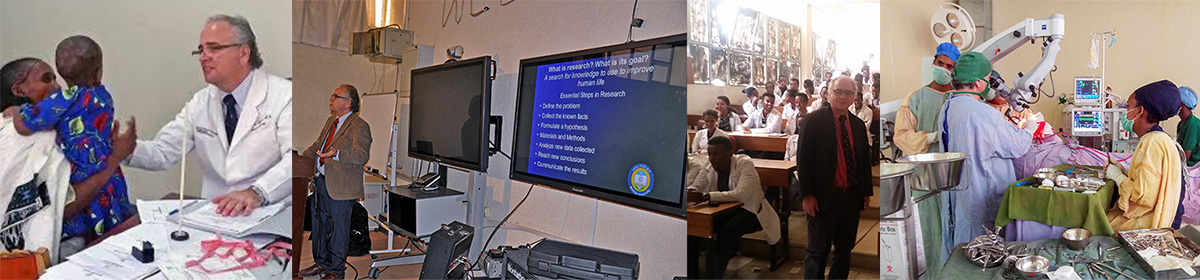

The academic new year at Mekelle University for residents (doctors who have graduated from medical school and now will undertake several years of specialty training) is just a few weeks away. They will transform from the theoretical and observing from the sideline to actually being involved in medical care to improve the quality and longevity of their patients. A part of the new experience will be their discovery that there is a limit of resources even in the richest countries and of course more severe in the developing countries. This same thing is happening not just in Mekelle, not just in Ethiopia, but around the world in all the teaching hospitals.

Although we like to pretend otherwise there is no escaping the inevitable fact that we are mortal and will at some point suffer significant illness followed by death. An Ethiopian diaspora calculated based upon the year 2000 that the per capita lifetime medical expenses where $316,000 in the state of Michigan (USA). Most of the cost occurs in the first year of life and after age 50. Women were more than men because they live longer. About one third occurs in middle age and about one half in the senior year of life.

It is hard to put a measure on the value of human life.

When discussions occurred about the use of dialysis as to whether should be payed for by government, analysts determined that spending $50,000 to give an additional year of quality life was worthwhile. This same measure was applied by several governments world wide. The actuarial value of a human life in developed countries is put somewhere between $ 500,000 and ten million dollars by actuarial experts. It is much less in developing countries where the economic output of an individual is much lower often less than a few hundred dollars a year.

The most recent budget for healthcare in Ethiopia was 1.4 billion dollar equivalents which cames out to about $14 per person for the approximately 100 million Ethiopian population. If you count out of pocket expenses it increases to about $24 per capita. This is of course much less than than the $4000-$5000 you see in European countries and the almost $10,000 in the United States. Yet even in these rich countries there are cries that funding is insufficient.

This means that physicians and the policy makers whom they advise have to learn to do more with less. They have to spend resources where they will have most impact. How are these decisions made? Medical ethicists talk about years of productive life as a reasonable way to compare, for example, spending money to help newborns versus the elderly. But not all cultures would agree with this concept totally. There is often a belief that older citizens should be rewarded for their service to society. Note the creation of Medicare and Social Security and its equivalents in the United States and many other developed countries.

Good medical care even in this age of limits is possible. It requires a sound knowledge of likely outcomes, compassion, and realistic communications with the patients and the community at large in both developing and developed countries. The inevitable consequences of our mortality and economic reality of limits leaves no room for anything other than truthful sincerity.