Given the already highest incidence of neural tube defects measured globally present in Ethiopia it would seem exceedingly urgent to immediately call for the cessation of use of Valproic acid, which has been shown to cause neural tube defects, in women of child bearing age in Ethiopia except for special circumstances.

History of Valproic Acid

Valproic acid was first produced in 1882. At that time its discoverer did not imagine that would be any therapeutic use because it was thought to have no pharmacological value. Then in the 1960s it was begun to be used in France and then in the late 1970s was approved for use in the United States as a primary drug for first epilepsy and then also for migraine headaches as well as mood disorders.

Over the next thirty years, however, concerns began to be raised about the potential relationship of the drug and birth defects. Both a joint European study and a separate French study showed that women of child bearing age taking appropriate therapeutic doses of 1000 mg a day or more had a high incidence of neural tube defects and other malformations up to seven times higher than the control population.

Valproic Acid Use in Ethiopia

The use of Valproic acid is relatively new in Ethiopia in just the last few years. A review of the treatment of epilepsy from Gondar University showed that 4.84 % of patients were using it. In addition it is being used to treat mood disorders and migraine headache to an unknown extent. The prescription of this medicine is relatively unrestricted and can be done by general practitioners and even non-physician health care providers. Unfortunately the official formulary for Ethiopia briefly mentions that pregnancy is a contraindication and suggests consideration for folic acid supplementation should be given to reduce the risks of birth defects. However a recent animal model study using chick embryos showed that supplemental folic acid for neural tube defects caused by valproic acid was not effective in prevention.

Neural Tube Defects in Ethiopia

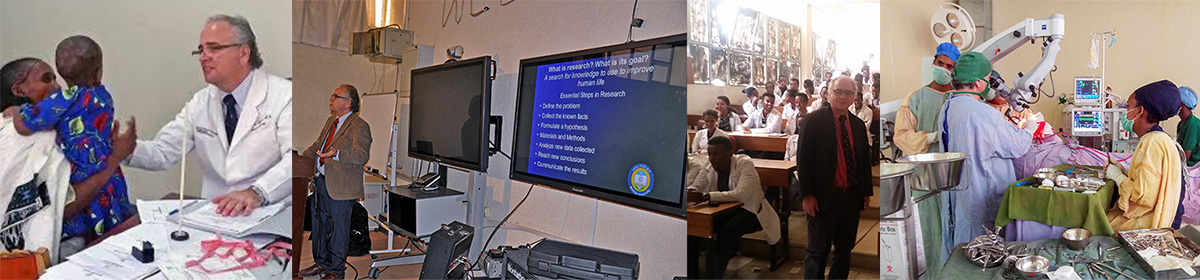

Our research at Mekelle University looking at the incidence of neural tube defects in the Tigray region of Northern Ethiopia suggested an over all incidence of at least 130 per 10,000 births but with some locals reporting close to 300 per 10,000 births. We know from studies done by the Ethiopian Institute of Public Health that 28% of women of children bearing age throughout Ethiopia have a significant folic acid deficiency which is likely the strongest contributing factor to the high incidence of neural tube defects

Recommendations for Valproic Acid Restriction in Ethiopia

1.Given the already highest incidence of neural tube defects measured globally present in Ethiopia it would seem exceedingly urgent to call for the immediate cessation of use of Valproic acid in women of child bearing age except for situations where no other drug can be used and the patient is receiving implantable or injectable forms of birth control.

2. Prescription of Valproic acid should only be done by physician sub-specialists in neurology, neurosurgery, or psychiatry and should require extensive counseling to the patient.

3.The formulary of Ethiopia should be modified and vigorously amended to warn of the risks. Although consideration for folic supplementation is appropriate it should be clearly stated that such supplementation may not be effective in preventing birth defects.