Ethiopia is facing a potential unprecedented crisis from coronavirus and how she responds is complicated by factors in her culture, traditions, geography, economics, and history.

In 1963, I was an elementary school child living in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas when I first learned about hurricanes. My father, a neurologist-psychiatrist, told us that a bad storm was coming. We had to take precautions and ride it out. This was perhaps the first time in my life I had to deal with uncertainty. Although my father looked confident I could sense that we could not know exactly what the future could bring. Hurricane Beulah hit with high winds and much rain destroying much of our town. I thought the howling winds would never end.

Now more than 50 years later I am in Ethiopia facing another type of storm. We have seen the storm form in China, attack Europe, and now with a few cases in Ethiopia it is knocking at our door. Ethiopia where I have lived since 2012 has had her share of calamity. She is an ancient civilization extending perhaps more than 10,000 years before the birth of Christ. Over the past century she has seen multiple attempts at foreign invasion, famine, and civil war. Yet her traditions and strong sense of spirituality tied to organized religion have always seen her through adversity.

As an academic physician and member of the medical faculty of Mekelle University I am very concerned and once again feeling that same sense of uncertainty I did so long ago. How will she face this new dilemma?

The Risk of Epidemic in Ethiopia

Moritz Kraemer, epidemiologist from Oxford University, has identified Ethiopia as one of the countries in Africa most at risk based upon an exhaustive analysis of asset the country possesses or not. Now that Ethiopia has several cases documented in Addis Ababa, what are the risk for spread? Adam Kucharski and his group from the London School of Tropical Health and Hygiene predict from a pre-printed study that when a country like Ethiopia has at least 3 confirmed cases there is 50% chance for the infection to become endemic and spread.

The Effect of Culture,Economics, and Geography

Africa accounts for 16% of the world population but only 1% of health care expenditures. With a 100 million population Ethiopia is the most rural country on the globe with 88% living in the countryside. Many families have incomes less than the equivalent of $20 per month. It may take hours to a day or so to seek medical treatment in a poorly equipped countryside clinic. There is little public health education with 75% of the women and 45% of the men being illiterate. There are few hospital beds (0.3/1000) population, few doctors, and limited diagnostic facilities.

Most Ethiopians do not travel outside the country but Addis Ababa, the capital, is one of the busiest airports and hub of Ethiopian Airlines which has daily flights from around the world including China and Europe. There is little doubt that this was the vector which introduced coronavirus to the country.

Ethiopians are a “touchy feely” culture like the Italians who are so troubled now. While there is little in the way of a government social safety net the people typically depend upon long standing bonds with extended family for emotional and financial support through hardship. Community interdependence is the rule. It is not unusual for people hospitalized to have many visitors and always also to have attendants (family or friend) stay the night helping to care for a patient. Trying to impose social isolation or even just social distancing will be difficult if not impossible.

The economic principle of scarcity, meaning that great value may be placed on resources which are scarce, is strong in Ethiopia. When going to the bank, airport, market, and clinic they frequently are a bit pushy because of a fear that what they are there for while run out before they get their chance. This is no doubt a left over from the Imperial and Derg times leading to distrust of authoritative promise.

When one sees the vastness of Ethiopia, about the size of Texas, and difficulty with transportation, an initial impression is that perhaps the virus will stay only in Addis Ababa. Unfortunately, that lesson was answered years ago when the HIV epidemic started with just a few truck drivers delivering goods throughout Ethiopia.

Typically when Ethiopians who are Orthodox are sick, they will often seek spiritual healing through church services, blessings, and consumption of Holy Water. In fact, every month I have patients with curable brain tumors who presented late only after pursuing this spiritual method.

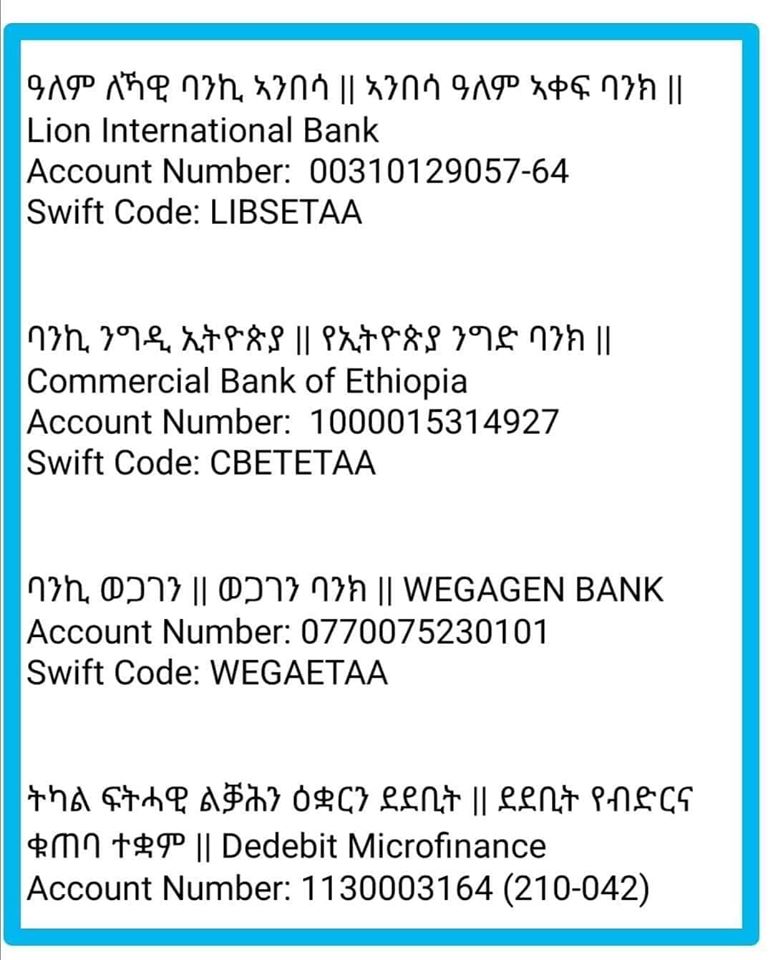

Many regions of the country have no reserve to deal with pandemics. For example the Tigray Regional Health Bureau only has a budget of 500,000 birr ($15,000 USD) to deal with a potential coronavirus epidemic. The cost of a single coronavirus is test is currently $ 500 USD. The government must try to seek payment from the patient as it cannot sustain doing testing without it.

There are not more than 200 functioning ICU beds with ventilators in Ethiopia. The experience in China, Japan, South Korea, and Europe have shown that if 50% of the population becomes ill, out of that about 20% will require hospitalization, and maybe 10% will need ventilator support. Unfortunately there is no way they will be able to treat 5,000 patients on ventilators.

What Will Happen to Hospitals?

Coming out of the Imperial and Derg times when social institutions like hospitals were rare and for the upper castes they are now seen as pillars of society with an implied unobstructed access. The CDC and WHO call for restricted entry to hospitals as well as the segregation of coronavirus patients to alternate facilities could provoke misplaced fears in the population. There will have to be a clear and repeated message explaining the scientific reasoning and how such measure are really best for the population.

Just like when I was a small boy, I cannot know exactly what will happen. I will stay in Ethiopia, the country and her people I have grown to love, and pray she finds her way through this test.