The paradox of children of Eritrean refugees promoting oppressive government their parents left now explained by research of postmemory formation and chosen trauma recall manipulated by propaganda. The explanation lies in understanding how a subsequent generation of survivors respond to their parent’s trauma. The concepts of postmemory and chosen trauma have been recognized in this group and manipulated intentionally by the Eritrean government. Researcher, Nicole Hirt, of the German Institute for Global and Area Studies discusses this phenomenom .

In the aftermath of the Jewish holocaust imposed by the Nazi regime Harvard researcher, Marianne Hirsch, developed the concept of postmemory which affects the second generation of a population who has suffered a significant trauma which she published in The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. This memory is not a memory of primary experience but it is a perception of the first generation after trauma which is “mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation”.

In Hirt’s research published in May 2021 she outlines how the intense lobbying of the Eritrean government of the first generation after the bloody Eritrean revolution have effected the development of “postmemory” which selectively chooses favorable trauma to recount and painful trauma to be forgotten which has come to be known as “chosen trauma”. The combination of frustration that things will likely never change, that one’s parents generation did not sacrifice for nothing, and the concentrated effort of savy propaganda by the Eritrean government on this generation has created this paradox.

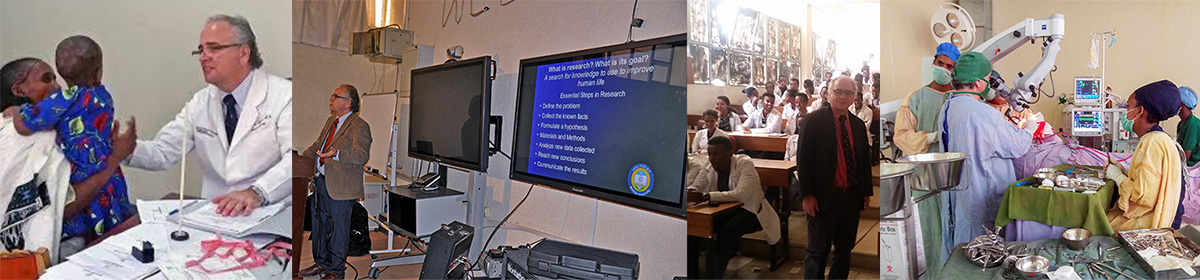

As a medical student at Harvard I became fascinated with how the brain functions then as a neurosurgeon learning about how the brain functions to facilitate language became extremely important as we did want patients to lose speech and communication from brain operations. We know that language, communication, relationship building, and memory are all tied together. Memory is not a perfect system and is affected by the need to create reliable relationship systems. As a neurosurgeon who practiced in Ethiopia for 10 years of which seven was in Tigray I have seen hundreds of Eritrean refugees referred by the International Organization for Migration, United Nations, and the refugee camps. I can attest to their exposure of torture and deprivation.

Over the past few years as a neuroscientist an extension of my research has been understanding that language and communication evolved in humans as a part of our need to secure relationships which improve our survival. Conversely we have an innate tendency to also avoid relationships which we perceive as threatening. Working with international NGOs at Mekelle University we began a program to help business students from Tigray who had problems adapting to international culture to learn basic concepts in communication and language principles based upon these neuroscience realities applied to creating functional and useful techniques.