In building neuroscience and neurosurgery at Mekelle University I experienced great happiness in serving the people and training future neurosurgeons and scientists. My seven year experience at Mekelle University serving the people of Tigray and surrounding areas as well teaching neurosurgeons and neuroscience gave me a new perspective on what is true career success. I now recognize there are three phases.

When I first came to Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in 2015 my initial goal was get a good neurosurgery service going. They were really the only government hospital capable of developing this goal outside Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, as well as being some distance north so it would offer chances to treat patients who would otherwise go untreated. The University and hospital were committed to building not only quality and quantity of good health care for Tigray and surrounding regions but also to medical education.

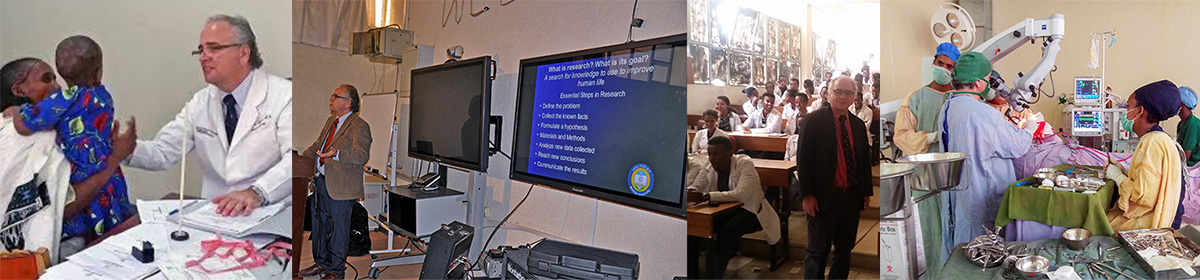

Initially I helped teach neuroscience and clinical neurology/neurosurgery to medical students and general surgery residents (young physicians who have graduated from medical school now doing specialty training) basic neurosurgical skills involving mostly traumatic injuries. My goal was to create a neurosurgery training program as well as a neuroscience research team.

After about a year working with Ethiopian Ministries and some good collaboration from the Ethiopian ministries, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies, and Mekelle University faculty we started a five year training program and a three year fellowship program. Up until the Tigray Ethiopian conflict we had grown to 18 trainees, doing 1,500 operations year, and published internationally recognized research with our multidisciplinary research team on neural tube defects which occur in a high incidence in Ethiopia.

Going through this experience made me reflect on what has been important in my career. When I was a college student at Texas A&M, then a medical student at Harvard, and finally a resident at the University of Miami I was mostly focused on personal achievement and perhaps also personal recognition. Through out that experience and subsequent practice I saw my career as having two phases. Learning to be a neurosurgeon and then becoming a great neurosurgeon. However it was my experience at Mekelle University and Ayder Comprehensive Hospital that taught me there was still a greater accomplishment which was to train great neurosurgeons and neuroscientists.

At first it was struggle. The hospital had little experience with neurosurgery. As a 60+ year old guy I was in the hospital every night doing surgery with young general surgeons and then residents with whom we had to start from scratch. Still they were eager to learn. With help from Indian and the few Ethiopian neurosurgeons we got up to date textbooks for them to read. Even though English was their second language they became proficient. At the end of the first year they knew more than I did at their level some 40 years ago.

During surgery they have to learn about anesthesia, positioning, hand control, to make movements less than millimeter which could mean life or death, how to control bleeding, how to do a 12 hour operation, and much more. We began to have weekly seminars on very complicated ideas where they absorbed the concepts so well I was learning as much they were. We were organized as most neurosurgical services in a sort of military style hierarchy to which the residents responded to well. Very quickly good and close relationships developed not only with those that were Tigray but also with others from other Ethiopian regions and other countries in the program.

I formed strong relationships with the research bodies of Mekelle University and we created a strong multi-disciplinary research team on neural tube defects which lead to meeting with government and World Health Organization officials, international NGOs, and a finally the beginning of a nationwide plan for prevention and treatment.

Before the Ethiopian occupation and blockade shut the neurosurgery training program down we had operated on more than 5,000 patients from not only Tigray but also Amhara, Eritrea, and occasionally Addis Ababa to Gambella. This week far away from Mekelle I had been doing the “paper work” for my first graduates. I wish we could have had a formal ceremony but I had good voice communication provided. Now I have learned that the best phase of a neurosurgeon’s career is seeing his trainees carry on and expand what I started.

I pray God will see fit to facilitate Ayder Comprehensive Hospital and myself to return to its service, teaching, and research missions once again.