My experience in Ethiopia has taught me that how the people of Addis Ababa see Ethiopia is often from a much different perspective than how those in other ethnic groups living outside Addis Ababa especially those not Amhara see the country. This creation of a capital identity group versus a regional identity group plays a role in understanding the current Ethiopian conflict. The different perception of an Ethiopian identity creates an ideological conflict that is difficult to overcome.

I have lived in Ethiopia since 2012 functioning as an academic neurosurgeon training students, neurosurgical residents, fellows, acting as an advisor, as well as doing intense research on the scourge of neural tube defects. Initially I lived in Addis Ababa, the nations capital, then in Dessie in the Amhara region and then since 2015 in the capital of the Tigray region, Mekelle. When I moved away from Addis Ababa, still for many weekends I would travel to Addis Ababa to see patients and also do consulting for NGO development, business interests, and government health concerns. In both Amhara regions and the Tigray region I made trips to the countryside rural areas to meet with the rural people to try to understand how they live and what contributed to the incidence of neural tube defects for which I helped create research sites throughout Tigray and recently trying to establish in Oromia which was interrupted by the war.

The creation of monarchial command center

Addis Ababa is a relatively new city. Although there was some settlement there by the Oromia who called it Finfinne its urbanization began when the Ethiopian Amharic Emperor, Menelik II, moved there in the late 19th century to create a more centralized command post to control his domain that extended much farther south then northern Ethiopia. As has been well written about about the capitals of many developing countries, Addis which is the short term used by locals, became more cosmopolitan then other areas. A large influx of Amhara gradually moved into what had previously been Oromia. They encouraged the development of educational institutions, commerce, diplomatic interaction, and modernization of the city which rapidly outpaced that of the other areas of Ethiopia.

Immigration from many regional states to Addis Ababa blends into a city identity

Immigrants from every region of Ethiopia came seeking work and opportunity they could not find in the countryside. Whereas in the countryside, which makes up the largest percentage of a rural population in the world among countries, lived a life less cosmopolitan and urban. While inter-ethnic marriage became very common in Addis it rarely happened and is often shunned in the countryside. The everyday language and identity in the countryside is the local one whereas in Addis those who were born and raised there identify themselves commonly as from Addis Ababa adopting Amharic as their main language and the Addis identity. They transform from their local ethnic culture to the Addis culture in one generation.

The current generation who was born in raised in Addis Ababa or went to university in Addis Ababa is more likely to accept the idea of a national identity to Ethiopia which makes a very small percentage of total Ethiopian population. Many have never been to the countryside and cannot relate to it other than it was where their ancestors grew up. This division of identity and experience no doubt plays a role in what is happening in Ethiopia today.

Those living in Addis Ababa have been raised with and most easily accept the idea of single Ethiopia identity predicted by such western social writers such as Levine. On the other hand researchers who spent time in the country side such as Young see Ethiopia as an empire of differing nations prone to recurring conflict.

The autonomy of the regional states and regional educational development empowers regional identity

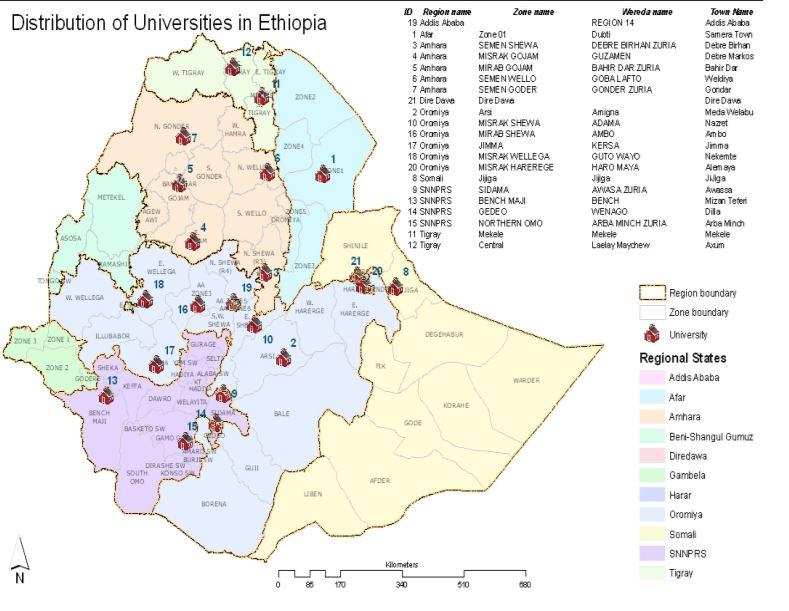

Since the post Derg era began all the regional state capitals have had universities built. Although initially they were staffed by mostly Amhara faculty that is giving way to more regional ethnic faculty. Many of these faculty have had to chance to study abroad or least cooperate with international institutions.

Over the past several decades thirty-three universities have been built in the many different regions of Ethiopia. Whereas the center of intellectual development was in Addis and primarily dominated by Amhara now there is a new spring of ideas and identity perceptions arising in each region. Thus new growth of regionalism is a strong counter to centralized Addis Ababa identity which promotes one national identity. Instead of all regional leaders going through a transformational experience of living in Addis Ababa for a time during their education that may alter their identity they are now being educated in regional universities by increasing regionally trained faculty and influenced by regionally experienced elders of the community.