Ethiopia is facing a growing crisis in infant meningitis compounded by a false reliance on the power of antibiotics to treat the problem without definitive diagnosis and follow up.

A growing problem

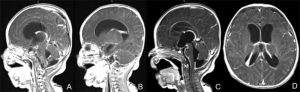

As you may know north eastern Africa including Ethiopia is part of the so-called “meningitis belt” with the highest rates of bacterial meningitis in the world. Just a couple a months ago I was attending a meeting with Ministry of Health with the new five pediatric neurosurgery centers of excellence in Ethiopia where a new growing epidemic of chronic meningitis seen throughout the country was discussed. Over the past year we are seeing more and more cases of infants on an almost daily basis presenting with progressive hydrocephalus who have diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid consistent with chronic meningitis. Our average census is 5 to 8 in hospital all the time whereas a few years ago it was only one or two. Many of these children have hospitalizations of 12 weeks or more. Many have died and many are left with significant cerebral disability which could have been prevented by earlier intervention and appropriate treatment lengths.

Systemic deficiencies

While this epidemic seems to be worsening, Dr. Abreha (Head of Pediatrics and Pediatric Neurologist at Mekelle University) and myself are concerned that deficiencies in facilities and procedures within the medical system may be contributing to it. Unfortunately throughout Ethiopia almost no lumbar punctures are now done to diagnose meningitis. A sample inquiry of pediatric residents and interns found that 75% of them had never done a lumbar puncture. Additionally many clinics and hospitals do not even have lumbar puncture trays. A false sense of security exists that powerful antibiotics given a short period time can will solve the problem

Secondly, the lack of ability to process or even receive an CSF specimen for analysis beyond 5 PM forces the treating physicians to start treatment without first obtaining a culture which is against world wide standard of culture first then start treatment. This seems very contrarian to the frequent theme of the pharmacy and laboratory professionals in Ethiopia that there is abuse of antibiotics.

A key analysis is determining the glucose, protein, and cell count in cerebrospinal fluid. Dr. Abreha recently gave a sample of tap water to the laboratory to be tested on the automated machine and it diagnosed multiple WBC consistent with meningitis. The equipment supplied to Ethiopian hospital is not capable of accurate diagnosis. Technicians can do manual counts but these are time consuming and labor intensive. This inaccuracy has greatly impaired our ability to determine if patients are infection free which they must be before they can undergo definitive treatment for hydrocephalus which is a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Thirdly, around the world there is much controversy about for how long antibiotic treatment should be given ranging from 10 days to 21 days. The problem is that partially treated meningitis patients who have not been cleared from the infection often do not have fever, meningeal signs, or other clinical findings except hydrocephalus. Many infants are briefly seen for nonspecific fever and receive short courses of antibiotics in Ethiopia without specific diagnosis being made and without adequate follow up. Many of these children we believe are harboring these low grade chronic infections leading to their late appearance at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. This creates a great dilemma as these children often require treatment of intravenous powerful expensive antibiotics from 21 days to in excess of six weeks or more until the infection is cleared by the demonstration of two negative cultures off antibiotics and normal cell counts. In addition in order for the shunt to work the protein has to be less than 150 mg/dl. Failure to diagnose an active residual infection before a shunt placement will only aggravate the infection leading to shunt removal and complications.

The treasure and future of Ethiopia is in her children. Meningitis appropriately treated early and followed can have a very low morbidity and disability outcome. The current situation if not acted upon will result in increasing medical costs, increasing disability, and increasing infant death which could be prevented with simple directed community and institutional action.

Recommended Course of Action

1. Immediate upgrade of laboratory ability in hospitals to receive CSF specimens 24 hours a day for culture, gram stain, sensitivity.

2. Training of interns and residents in performing lumbar puncture and making sets available

3. Institute an Ethiopian wide policy of obtaining CSF before starting antibiotics. Children with seizures, lethargy, focal deficit, or signs of increased intracranial pressure would be emergently sent to a referral hospital for CT Scan or if possible if they have an open fontanelle undergo an head ultrasound locally to rule out mass before lumbar puncture.

4. Make sure all children treated for meningitis undergo follow-up and that a repeat lumbar puncture is done after treatment. This may seem over kill but given the crisis happening it is the only way to prevent these chronic cases.

5. Funding of community service, public education, and research projects on this vital issue in cooperation with the regional health bureaus.

6. Training of health officers, nurses, and general practitioners in proper diagnosis, evaluation, treatment, and referral of children with meningitis and hydrocephalus.