The path to becoming a neurosurgeon in the developing country of Ethiopia begins in primary education and progresses through a gauntlet of achievement challenges through early adulthood. Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the teaching hospital for Mekelle University, is currently training 16 neurosurgeons for Ethiopia and surrounding countries.

As children they often grew up in a multi-generational house without electricity or running water. Time to travel to and from school everyday is measured not in minutes but in hours. Before and after school they have to help maintain the house and family income such as caring for livestock, farming, or doing labor.

When they go to primary school they initially speak the first language they learned from their family (Tigrinya, Oromifya, Sedamo, Afar, Grogi, etc.) but must then learn Amharic and English progressively in elementary and secondary school. If they are lucky enough to have a television set watching it can give an advantage to learning English. To get a chance at college they must show significant reading and writing skills in the three languages by the 10th grade.

At the end of their 12th year of secondary school they have to take a national competitive exam. Science and most studies in university are taught in English so competence is mandatory. The top scorers get a chance to attend medical school for a little over 2000 places currently.

For six years in medical school they are apart from their families for the first time. Living in crowded concrete dormitories with frequent water and electricity shortages, bedbugs, and a monotonous diet of little else but shir0 with enjera are common experiences. The last year of medical school they function as an intern which is really on the job experience that is very demanding in terms of hours and responsibility.

To get into a residency program to become a specialist requires getting a sponsor, usually a university or regional health bureau, and then competing for the few hundred slots by interview, grade record, and more testing. For example in Neurosurgery last year there were 21 slots only for the whole country. If they get into specialty training, the pay is poor, less than a hundred dollars a month and they have to find some kind of housing. Usually they end up renting a room in a house for sixty dollars a month. They will work 12+ hours a day and have to spend the night in the hospital about every third or fourth day working all night to care for patients. The training program lasts five years with one month of vacation per year.

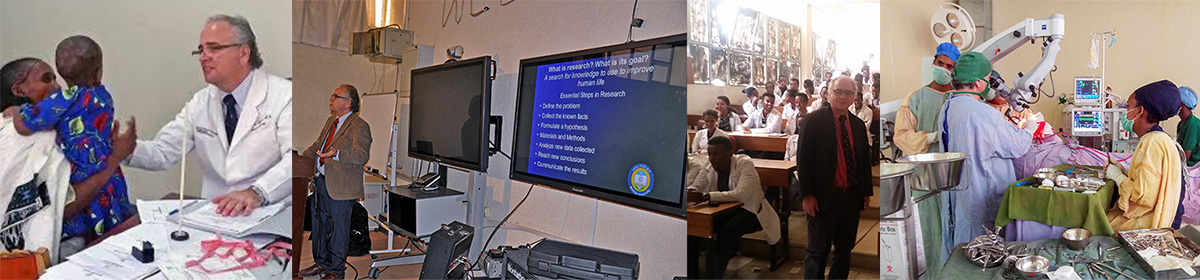

The modern concept of physician training is that it is a triad of knowledge (basic science and clinical medicine), skill (examining patients, interpreting diagnostic tests, surgical skills, etc.), and professionalism. In the first year of training they have to learn how to care for trauma patients and critically ill patients. During this year they have to master the basic skills of general surgery before they can formally begin neurosurgery.

From the second year through the fifth year they have to learn the equivalent of a PhD in neuroscience, be able to save a critically ill patient, finely interpret magnetic resonance imaging and CT scans, master fine technical skills with eye hand coordination greater than the finest musicians, and demonstrate capable leadership skills to lead medical teams to save lives. They need to read about and comprehend about 500 to 800 pages of books and journals every three to four weeks.

Around the world, the British model of training surgeons has been adapted which is what we call competency based. Neurosurgical residents progress from watching how patients are cared for and undergoing surgery at first and then progressing to less and less supervision. Every day they are constantly challenged by not only the diseases they are treating but by a strong Socratic method of teaching requiring them to always explain and justify their every decision and action. Gradually they reach a point where they function with distant supervision which is the real measure of their capability. By the end of their training which has averaged evaluating a hundred or more patients in a week and participating in surgery on about 5 to 7 per week such that they have seen thousands of patients and participated in thousands of surgeries they will be competent neurosurgeons.

Hello sir

First i want to tell you how much i appriciate and admire your efforts to create new neurosergeon generations.You are so wonderful.We are so lucky to have you in our country.I personally have a goal to become a good nurosergeon.I am a female but i don’t care about my age going old through learning.Since this is my goal i will try my best to pass challenges that come through on my way.I want to be like you.I wish i will get a chance to meet you someday.Thank you Sir.