At Mekelle University Department of Neurosurgery-Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital we have been developing an expertise in the treatment of stroke due to rupture of a cerebral blood vessel culminating in a successful clipping of a ruptured aneurysm.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage in Africa and Ethiopia

Stroke in Africa and more specifically in Ethiopia remains an almost taboo subject. It is shrouded in superstitious beliefs of curses and hidden poisons among most of the population who receive little public health education in what schooling they attend. A significant form of stroke is that due to rupture of a cerebral artery which creates the phenomena of subarachnoid hemorrhage. It is estimated that worldwide 9 in 100,000 years of human life or 1 in 50 people will suffer a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Although rupture of a brain artery causing subarachnoid hemorrhage may lead to sudden death there are many patients who if given advanced treatment can be saved and return to functional lives. To receive this treatment requires special trained medical centers with experts in emergency medicine, neurology, radiology, anesthesiology, and neurosurgery. Up to now these centers have been lacking in most of Africa.

How subarachnoid hemorrhage causes damage

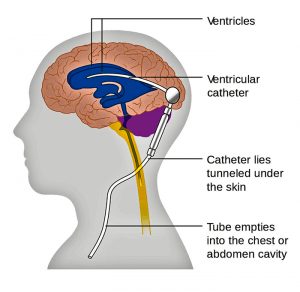

When a brain artery ruptures it may cause severe pressure on the brain which can kill or permanently disable. This type of large clot is unusual in most patients. Instead what happens is that the blood causes surrounding blood vessels to defensively constrict limiting the blood supply to the brain. This pathological process is vasospasm. Additionally the blood leakage can lead to chemical abnormalities of sodium or the mal-absorption of a fluid called cerebrospinal fluid which normal is produced and absorbed in a balanced way. Once a blood vessel ruptures once it will likely rupture again as each day goes by, a ticking time bomb.

Treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage and ruptured cerebral aneurysms

Successful treatment of ruptured cerebral artery aneurysms requires rapidly making the diagnosis and beginning aggressive resuscitation of vasospasm and electrolyte abnormalities. The blood pressure must be closely controlled and the patients respiratory system supported. Upon stabilization the patient should undergo timely surgery or intravascular treatment to reduce the incidence of a second deadly rebleed. Whether microsurgery or intravascular treatment is better remains controversial.

A representative case at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

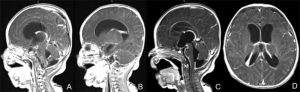

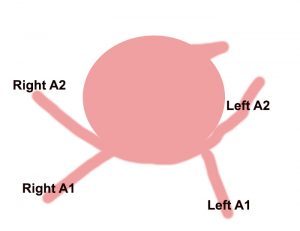

The following case is an example. A 55 year old Ethiopian grandmother suddenly complains of the worst headache of her life and goes into a coma. She is brought to Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in Mekelle, Ethiopia on the Mekelle University medical campus. Emergency physicians and internal medicine specialists stabilize her condition and perform a CT Scan which shows subarachnoid hemorrhage and suspician of a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm.

The patient is comatose with electrolyte abnormalities and out of control high blood pressure. She is admitted to the medical intensive care unit where she receives supplemental oxygen, high doses of fluids to correct hyponatremia and try to overcome the vasospasm, as well as a special medication, nimodipine, which can help to counteract vasospasm.

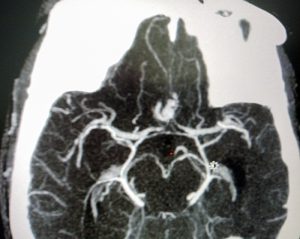

After 2 weeks she regains consciousness and a repeat CT angiogram ( a special CT scan which shows the arteries of the brain in detail ) is done which now clearly shows a 5mm aneurysm. Now that she is stable surgery must be done soon before a fatal rebleed can occur.

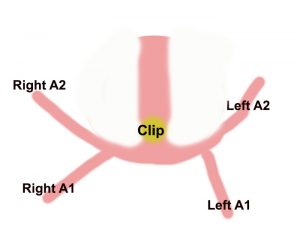

She is taken to the operating room with a specially trained anesthesia team which finely controls her blood pressure during surgery. An opening is made in the front and side of the skull while under general anesthesia and carefully working under the brain the ruptured blood vessel is exposed and clipped to prevent rebleeding.