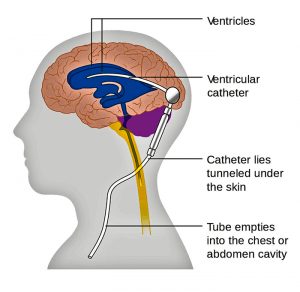

Traditionally surgery for hydrocephalus has been performed by neurosurgeons who undergo vigorous neuroscience basic training and supervised surgical experience of at least 5 years in length (longer in developed countries) after medical school. Recently there has been some discussion as to whether in African and other undeveloped countries general surgeons should be taught to perform ventriculoperitoneal shunts to treat hydrocephalus. The treatment of hydrocephalus should remain under the direction and in the hands of neurosurgeons.

Hydrocephalus as a medical condition has been recognized since the time of the ancient Greeks. The concept of surgery to treat hydrocephalus by diverting the flow of cerebrospinal fluid began in 1949, when Nulsen and Spitz implanted a shunt successfully into the caval vein with a ball valve. Between 1955 and 1960, four independent groups invented distal slit, proximal slit, and diaphragm valves almost simultaneously.

An estimated 750,000 people have hydrocephalus, and 160,000 ventricular peritoneal shunts are implanted each year worldwide almost always by neurosurgeons. About 56,600 children and adolescents younger than age 18 years have a shunt in place.

The incidence of hydrocephalus in Africa is estimated to be 145 per 100,000 which is three times higher than in the developed world. Thousands of these children will need surgical intervention, either ventricular peritoneal shunt or the newer, but still not clearly accepted as superior, endoscopic procedures.

A survey conducted among African neurosurgeons in 1998 showed that there were 500 neurosurgeons in Africa; that is, one neurosurgeon for 1,350,000 inhabitants, and 70,000 km2. That number is significantly increased now but the exact current number is unknown. Worldwide the average is 1 neurosurgeon per 230,000 but in Africa it can be as low 1 per 9 million people. It is believed there are 700 neurosurgeons currently or about 1 per 1,238,000 people which is an improvement but still not nearly enough. Ethiopia currently has about 30 practicing neurosurgeons and will soon be graduating about 30 newly trained neurosurgeons per year. This means Ethiopia will need about 450 functioning neurosurgeons taking into account expected population growth.

Although the training of neurosurgeons in performing ventriculoperitoneal shunts has become somewhat standardized via the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies as well as international neurosurgical groups, the training of general surgeons to do this procedure has not been rigorously studied. There are very few publications about the results of general surgeons performing ventriculoperitoneal shunts but an a study from Kenya done in 2010 showed a significantly high complication rate of 65% with an infection rate of 9.1% and shunt malfunction rate of 11.1%. This was much different than reported by Dr. Warf , an American trained neurosurgeon who created a specialized center in Uganda, with a malfunction rate of 4%.

More recently endoscopic procedure to open the third ventricle to the cistern and coagulate the choroid plexus are gaining ground but not totally proven yet. These procedures clearly require specialized training and knowledge of anatomy of the caliber of a neurosurgeon and not a general surgeon.

The real issue was not really the shortage of surgeons but the bottleneck was lack of hospitals, operating rooms, and clinics. Additionally transportation to get healthcare is a real issue. Now Ethiopia has seen the light and has three training programs for neurosurgery in Ethiopia and are graduating about 30 per year. Again the problem is we have more surgeons than facilities to operate in.

African governments will see the idea of adding shunt placement to general surgery as an easy fix. In reality they are already overworked. I have taught medical students and general surgery residents. Many people think ventriculoperitoneal shunts are the easiest procedure but I always tell my neurosurgery residents and fellows it is not. Decisions about when to shunt, is the shunt working, is it infected? require experience and training. Academic following of outcomes, techniques, epidemiology requires an academic neurosurgery program take the lead.

Unfortunately there is no shortcut to capacity building. We are now training neurosurgeons for other African countries as well as Ethiopia. Eventually we will need more than 450 which will take time.

Finally I would say that our approach to hydrocephalus is changing rapidly. For us and the Uganda group we are consistently reducing the number of shunts we are doing each year. Whereas in the past we did nearly two hundred it is now going to be less than 100 even though we cover 20 million plus population with the highest myelomeningocoel rate in the world. We now recognize that many neural tube defect newborns have low grade infections which require antibiotics sometimes over 21 days until the csf is clear. Many times their hydrocephalus stabilizes after a few fontanelle taps. Although the post infectious group is rising ( we are in the infamous meningitis belt of Africa) similar we have avoided shunting by similar close follow-up. Our shunt infection rate is currently 3% because we identify these chronic low grade infections. I shutter to think what would happen if general surgeons with little experience are let loose upon this situation.